Firefighting in the Dependency Hell: a Case Study

Disclaimer

The following case study focuses on dependency management, omitting other details that are irrelevant to the topic or might be sensitive to share publicly.

I do not necessarily speak on my behalf. Let's assume some Product Owner (The PO) appeared in such a situation and acted a certain way to resolve the dependencies.

Background context

There are a few details to be mentioned to provide context:

- PO joined an ongoing project at its critical stage. Thus, there was no room for cross-organizational changes.

- PO had a flexible number of responsibilities, which might vary considerably from that of the vanilla Scrum product owner.

- PO had a great team; it would be impossible without them.

Dependencies structure

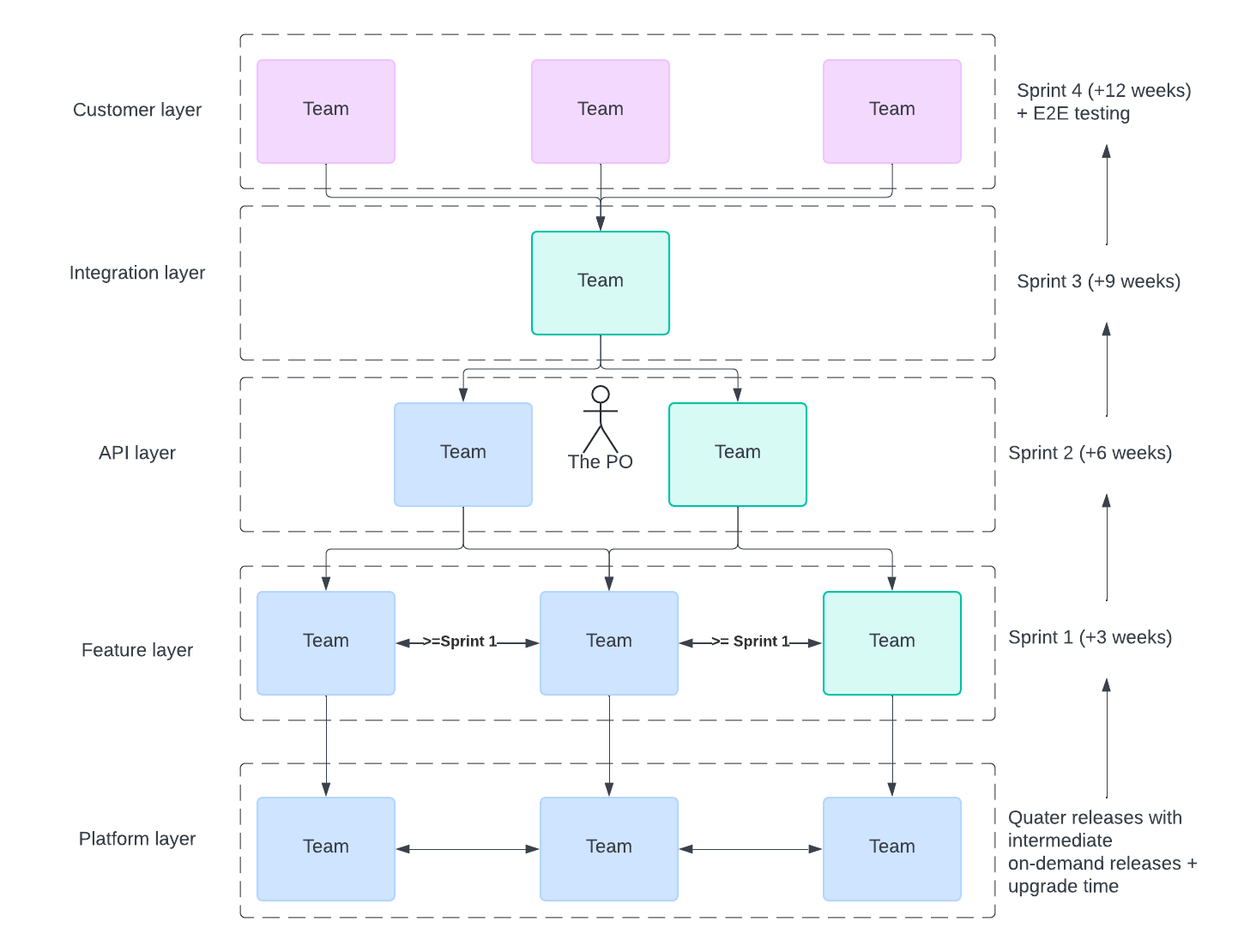

This is what the team topology looks like, approximately. And that impacted how dependencies are distributed.

Three organizations are involved, each with their own development teams and management. It is obvious that each side pursues its own goals in accordance with contractual obligations.

There are five architecture layers, with a number of teams on each layer. It is not described on the diagram (to keep it simple), but a team within the layer might belong to a different specialization, responsible for one or several microservices. Each specialization has its respective PO, Architect, Delivery Manager, QAs, BAs, etc. They have their own scope, backlog, and priorities.

They are, from bottom to top:

- The Platform layer provides the core capabilities of a system. It exists outside the project.

- The Feature layer uses, customizes, and extends the core capabilities.

- The API layer that exposes RESTful API to be consumed by upstream layers.

- The Integration layers consume those APIs and provide data enrichment from 3rd party services.

- The Customer layer utilizes the final output for its own purpose.

Our heroic PO is trapped in the middle, being on the frontline of their organization and managing the API backlog for two teams. We will look at dependency management from that perspective.

Horizontal and vertical dependencies

There are 3-week Scrum sprints, so a feature path through each layer takes much time. From the horizontal perspective, there are some scenarios:

1) Core functionality without deviation: starts from the API layer.

2) Core functionality with customization: starts from the Feature layer.

3) New Core functionality: starts from the Platform layer.

The Platform has its own per-quarter release cycle with an option to provide intermediate releases on-demand within a quarter. However, there is an additional buffer time (aka upgrade) to deliver a Platform release and ensure it works with the existing customizations.

So, case 3 is more unpredictable and depends on multiple criteria. Case 2 is the most common, so our story focuses on it.

Starting from the Feature layers, it takes four sprints (12 weeks) to deliver a feature to the top. Plus, we consider end-to-end testing and other production readiness procedures. So it might take even more time.

We also consider the Horizontal dependencies within the team in the same layer. They could work in parallel, but sometimes, they must wait for their peers. So delivery might be postponed even further.

Shrinking the gap

The first step will be prioritizing work based on the above-mentioned scenarios. First of all, the PO decides to identify and prioritize what is already available without any downstream dependencies. Next is what is available from the core but requires customization of the feature layer. And last, what is not present in the core must be delivered by the Platform.

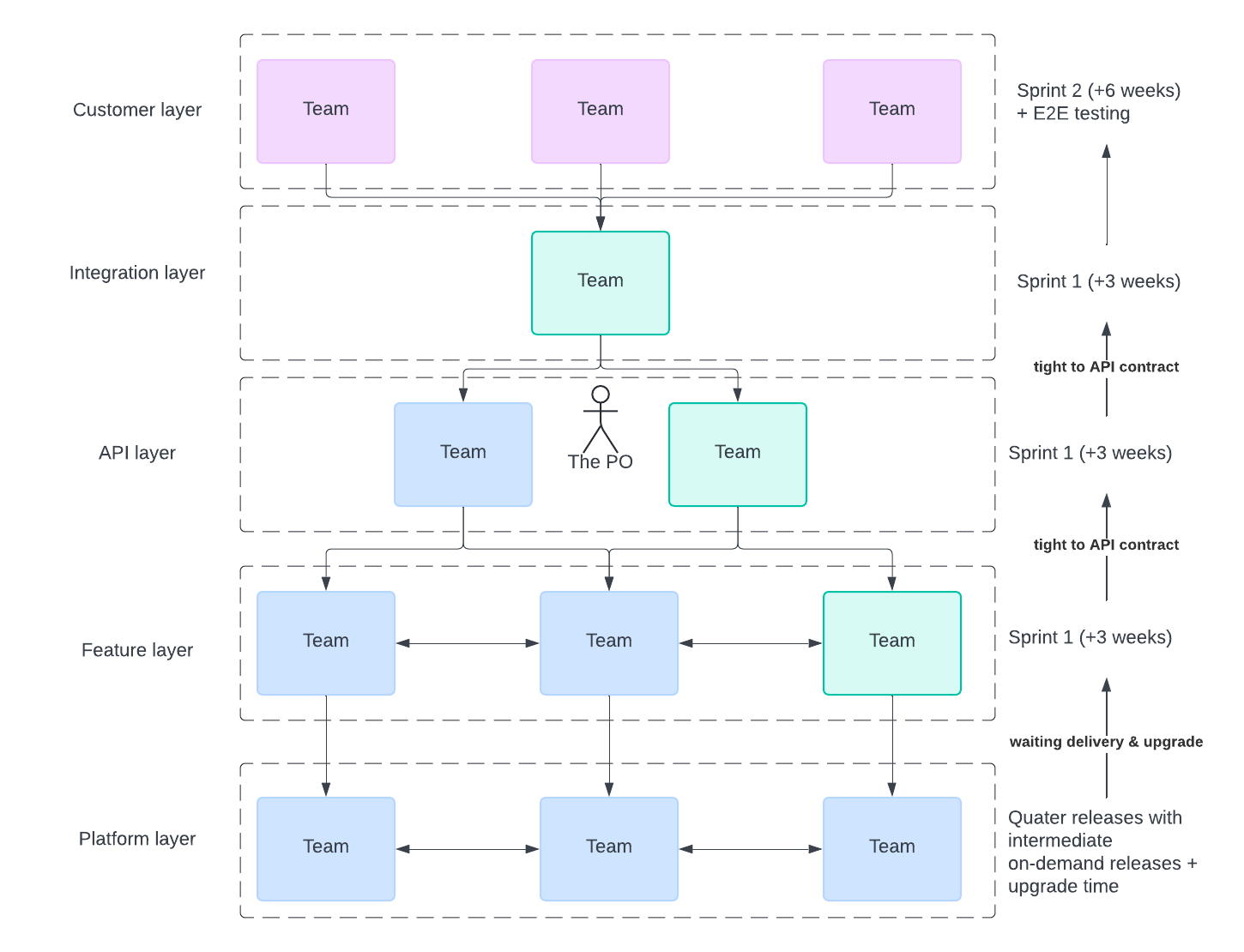

Secondly, we need to parallel the work to shrink the delivery timeline as much as possible.

In this case, it is possible for the API and Integration to work in parallel: the API teams provide an API contract for each future-coming API endpoint or expected changes for the existing one. Teams can implement based on the contracts but not merge into the main branch.

An alternative strategy would be exposing a mock API (i.e., API with mock data). That was a meaningful decision by engineering leads not to merge any mock code. We later discuss what downsides it would cause.

At some point, due to some postponements and waiting for new Platform core pieces, three layers are forced to work in parallel.

The API and Feature layers align on the API contract between them. And that is not the same API contract that exists. So, the PO has to manage two types of API contracts across the parties.

An advantage here is that all four upstream layers act as a Platform's customers, so they request a design that does not require customization and skip the feature layer. However, the Platform, having many customers, has the right to provide a generic solution, not a custom feature that suits one customer but another one.

Even though they managed to pack an ideal delivery timeline across four technology and organizational layers, the cost is high:

- Excessive communication and efforts to manage parallel work.

- Inevitable reworks and last-minute changes in the API contracts.

- Communicating and enforcing all parties to keep the API contracts.

- "Communal" testing that leads to multiple bugs.

- Late coming or missed requirements.

- Fighting "who owns what" as each organization pushes its own agenda.

That parallel work looks pretty good on paper, but that is a fragile construct that is far from smooth operation.

Art of extreme facilitation

The API layer has to identify requirements from the upstream layers and pass them to the downstream for further gap analysis to see whether a query fits one of three scenarios. The API team lacks the specialization knowledge that the Feature team does, and they both lack the Platform knowledge.

Being responsible for requirements, the API layer's PO has to communicate vertically between up and downstream to come up with a design that satisfies everyone and the server business needs of the customer. That means bringing everyone to one table and facilitating all parties to be productive and reach a particular conclusion.

Along with that, horizontal communication across teams in the same layers must be managed and facilitated as well. Different specializations often cannot align on something without a 3rd party facilitator, and the API folks fit that role.

After concluding the design, the next step is to make sure it is prioritized accordingly, both vertically and horizontally, and closely monitor any deviation from the plan. Those deviations are inevitable.

What if...

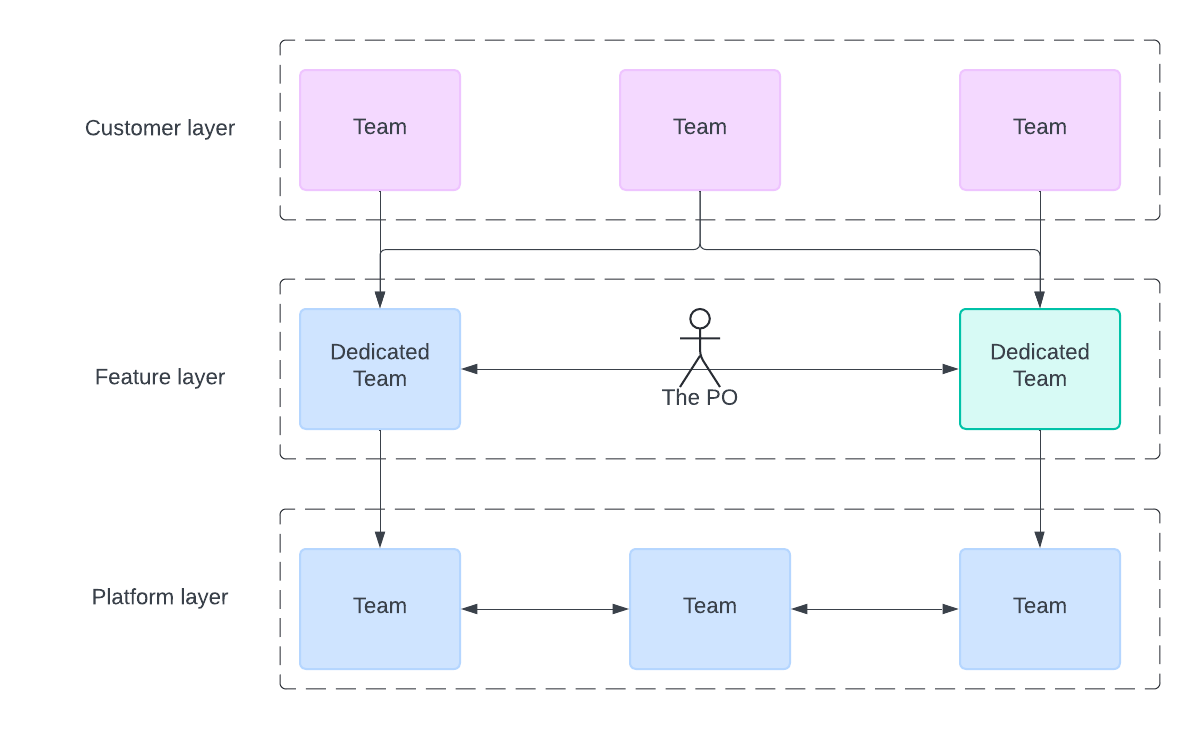

The PO thinks the main problem is the team structure, which complicates communication. Having five layers, where one layer is a bottleneck, is too far from being effective.

The Customer layer should merge with the Integration, and API with Features should make the cross-functional dedicated team serve API and core customization within the required specialization. That would require additional training and learning from each other, but it would benefit everyone.

The PO thinks that a dedicated API team is bullshit. And I can't agree more after reading the Team Topologies book (I wrote about it here).

The Platform remains a constant as it exists beyond the project, and there is not much to do with it from that perspective.

The PO would also proceed with mock API instead of API contracts even though it considers some additional development and testing efforts (make a mock, test it, replace it with the actual implementation, and test it again) and risks of forgetting to remove mocks. In the end, maintaining and communicating API contracts takes the same effort, if not more.

Conclusion

The current case study explores how having multiple layers complicates effective delivery and causes multiple dependency downsides and demanding commitments to the upstream. Any changes to improve the process with good intentions mainly intensify the agony and firefighting to communicate with all parties to resolve dependency in time.

The management should carefully structure teams before the project starts and consider some flexibility for further changes down the line. Major restructuring in the late stages would put the project at risk. Decide wisely.